Powering Electric School Bus Adoption with Complementary Funding and Financing Solutions

Because of the historic amount of grants and other funding available for electric school buses, funding is typically top of mind for stakeholders when considering the transition to electric. What about financing? And how can the two best work together to maximize the benefits of electrification?

The transition to electric school buses (ESBs) has the potential to bring air quality, health, climate, and economic benefits to communities across the country – and particularly to underserved students and communities who are disproportionately affected by vehicle pollution. Recognizing this, federal and state governments offer grant and other funding programs to help school districts and other school bus operators pay for electric school buses, which currently cost three to four times the price of a diesel bus.

Funding programs alone, however, will not be enough to drive electrification at scale for a U.S. fleet of nearly a half-million buses. Consider, for example, the first round of the new federal Clean School Bus Program which saw demand for funding that was eight times the available amount.

Funding can be paired with financing for vehicles and their charging infrastructure to extend public dollars further, bringing the benefits of electric school buses to more communities. Here we offer insights into why and how to complement funding with financing, turning on both spigots to help support greater adoption more quickly.

Funding is the awarding of capital to support a project, organization or initiative without the expectation of repayment by the awardee. It enables the recipient to cover expenses and achieve objectives outlined in their plan or proposal. Funders for school bus electrification include federal, state, local and tribal governments, utilities and philanthropy.

Financing is an arrangement that provides capital for costs today to be paid back over a future period, often with a small premium (interest). This enables districts to make cost-effective investments and spreads out payment over a longer period of time. Financing for school bus electrification could include a range of actors, such as private lenders, public lenders (e.g., DOE, USDA), green banks and a range of mechanisms, such as loans, bonds and leases.

Electric School Bus Funding

State and federal funding for electric school buses has grown dramatically in recent years, increasing from a total of $280 million allocated by 2020 to over $9.3 billion by 2023 (Atlas Public Policy, July 2023; WRI analysis, October 2023). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA’s) Clean School Bus Program, the Volkswagen Settlement funds, and state funding and voucher programs like California’s Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Program are some of the largest sources of electric school bus funding to date. There are also new federal tax credits that school districts can access for vehicles and charging infrastructure. Meanwhile, states such as New York, Connecticut, California, Maine and Maryland have passed transition mandates for school bus fleets to electrify, in some cases with accompanying funding – adding to the momentum for the electric school bus transition. The World Resources Institute’s Electric School Bus Initiative hosts a Clearinghouse that provides more information on these opportunities.

Policymakers can consider a variety of funding mechanisms to support districts and private sector operators in acquiring electric school buses, as outlined in Table 1.

| Type | Definition | Advantages for School District | Disadvantages for School District |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grant | An award made to qualifying applicants, for a specific purpose or use case, often with ranking based on set criteria. | Generally, directs aid to priority districts; often covers planning and project management costs. Funding may be received either before or after bus purchase. | Applications and reporting can be time intensive and onerous. |

| Rebate | A reimbursement after certain eligible purchases of pre-approved equipment. | Limited paperwork. A pre-approved equipment list reduces the burden on applicants and simplifies purchase decisions. | Traditionally, funding is received after bus purchase. Requires the recipient to pay full price at the time of purchase; lower-resourced districts may not be able to cover these initial costs. Alternatively, in some programmatic design, rebates can more closely resemble vouchers with pay out upon submission of a purchase order. This can help address any cash flow concerns. However, in acting more similarly to a voucher, a rebate could also risk inducing unintended consequences like inflated prices. |

| Voucher | A credit applied “on the hood” immediately at purchase that lowers the price paid by the recipient. | Least amount of paperwork. Funding received at time of purchase eliminates the burden of delayed reimbursement. | Pre-approved dealers apply the funding to the final price of the vehicle. Without proper tracking and reporting, it can induce unintended consequences within pricing structures. |

| Tax Credits | A credit on taxes and applicable to electric school buses. School districts may be able to access tax credits as a direct payment as tax-exempt entities. | Tax credits are provided to all who apply, as long as the applicant satisfies all the requirements. | Requires additional applications and tax filings that can add complexity for school districts that do not typically interact with IRS and state revenue departments. Funding received after purchase and after IRS approval of filing, potentially creating a need for bridge financing. It has the potential to be designed as a point-of-sale payment. |

Note: This table is not comprehensive of all funding mechanisms.

Funding programs alone will not be enough to drive electrification at scale for a U.S. fleet of nearly a half-million buses.

The Role for Finance to Complement Funding

Funding alone is not enough to bring the electrification of school bus fleets to scale. Public funding has reduced the expected timeline for when the total cost of ownership between electric school buses and their diesel counterparts will reach parity (i.e., the total cost of owning and operating the bus over its expected lifetime).

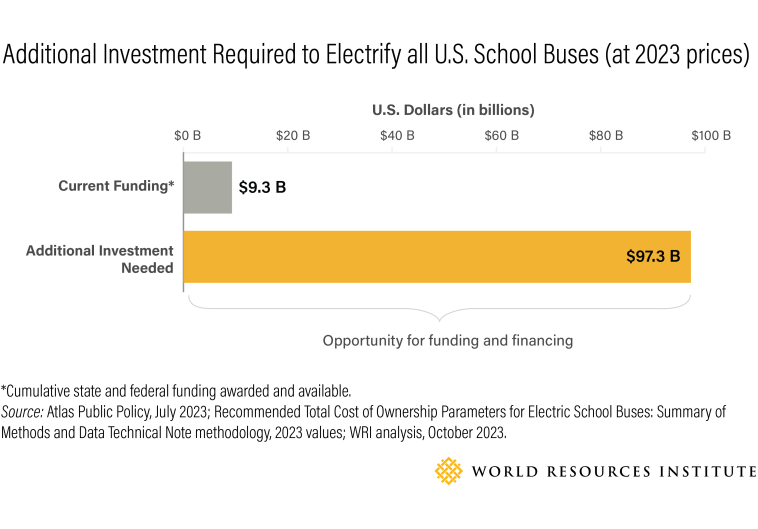

However, public dollars are limited for the total capital required to transition the full fleet of almost half a million school buses in the United States. The $9.3 billion dollars allocated by states and the federal government to date can cover up to 41,900 electric school buses at current prices. This is less than 10% of the U.S. school bus fleet, which is estimated to have 480,000 school buses.

Note: The estimated costs to electrify the remaining U.S. school bus fleet, 438,100 school buses, is approximately $97.3 billion based on 2023 bus prices (Recommended Total Cost of Ownership Parameters for Electric School Buses: Summary of Methods and Data Technical Note methodology, 2023 values). This includes $40,000 per bus to account for the IRA Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit (45W), and $113,000 per bus to account for school district budget allocation for the replacement of a diesel bus. Prices for electric school buses are expected to decrease within the upcoming years. Note that the 45W credit will be eliminated for any vehicle acquired after September 30, 2025. On August 21st, 2025, IRS provided new information about the term "acquired."

Funding programs are also finite in nature and not necessarily renewed over time. When designing a program to transition to ESBs, policymakers and practitioners should evaluate how combining finance with funding can extend public funds and support full fleet electrification and other goals at scale. By helping public dollars go further, policymakers can also help meet critical equity goals and direct limited public funds toward the districts that need them most.

Types of Financing

Policymakers can consider both public and private forms of financing to complement and extend the impact of public funds. Table 2 below highlights different financing mechanisms available, including loans, leases, and bonds, to support districts in acquiring electric school buses. Bonds, a type of public financing, have already been utilized by districts to help realize their electrification projects. For example, Austin Independent School District in Texas is using a bond to finance their school district’s transition to electric school buses. New York State also utilized a bond to raise $4.2 billion in capital to support new and expanded projects addressing pollution and climate change. $500 million of the Bond Act has been dedicated to funding for schools to transition to zero-emission school buses. However, it is important to note in this example of bond issuance it is the state that has utilized the financing mechanism, not the school district like in the previous example.

To date, of the few school districts that have employed financing to procure ESBs, bonds have been used more than other financial mechanisms due to their low-cost capital nature and school districts’ familiarity with issuing bonds for other capital projects.

School District Spotlight: Austin Independent School District (Austin ISD)

In 2022, the Austin Independent School District Board of Trustees unanimously approved a resolution to transition the entire bus fleet to electric vehicles by 2035. That November, the resolution received financial support through the approval of the $2.4 billion Austin ISD 2022 Bond, which was intended for financing construction projects and capital improvements for the district. The passing of this bond marked the largest bond in the city's history. Of the $2.4 billion, $25.7 million was allocated for the replacement of school buses.

The Austin ISD transportation department plans to fund the next round of electric buses through a mix of grants and the 2022 Bond and is looking to use the next bond for future rounds of electrification as well. This is a great example of complementing funding with financing. For those looking to electrify, Luke Metzger, the Executive Director of Environment Texas, recommends layering an electrification resolution with a key opportunity like a bond bill or election to help capitalize on a moment of change and political will.

Private lenders are also active in the financing space, such as the financial institutions associated with vehicle manufacturers that facilitate leasing and tax-exempt financing, as well as transportation and infrastructure services companies which embed financing in subscription fees. Additionally, inclusive utility investments offer an alternative financing mechanism for electric school buses.

| Type | Entities | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Private loans | Retail and commercial banks, credit unions, savings and loan associations, investment banks and companies | Type of private financing. Provides a wide variety of lending opportunities to individuals and commercial customers, including school districts and transportation contractor firms. Terms and conditions are set by the lender. |

| Public loans | State clean energy funds, federal institutions, green banks, community development financial institutions (CDFIs) | Type of public financing. Financial arrangement where the government or other public entity provides funds to a school district with the expectation of repayment over a specified period of time. Terms and conditions are set by the lender and may include project eligibility criteria to meet the lending entity’s fund goals. Potential for lower-interest rates than from private firms. |

| Public bond | Federal, state, tribal and local governments | Type of public financing. In most cases this is a municipal bond issued by a school district to raise funds from the public, typically through the sale of bonds, to finance educational infrastructure and other projects. Usually repaid through future tax revenues or other specified revenue sources. A bond for a school district typically needs to go to the voters for approval. |

| Leases | Original equipment manufacturer (OEM), dealers | Type of private financing. School districts enter leasing contracts directly with OEMs or dealers, which can include an option to purchase asset after leasing term is complete. OEMs can also offer low-cost capital to school districts if the financing mechanisms are tax-exempt. This means that OEMs’ interest proceeds are not taxable by the government. |

| As-a-service firms | Charging-as-a-service (CaaS), transportation-as-a-service (TaaS), infrastructure-as-a-service (IaaS), turnkey asset management | Type of private financing. Firms that offer transportation electrification services at a monthly or annual fee to school districts. These services may cover only the charging (and associated electricity costs) or may cover the bus, charging and operations. |

| Inclusive utility investments | Utilities | These investments from utilities in charging infrastructure and/or the on-board batteries of electric buses are recovered through a site-specific cost recovery tariff that is time-bound and is paid with the operational savings from switching from diesel to electric buses. These investments reduce the up-front cost barrier and promote more access to zero emission technologies. Inclusive utility investments are regulated by state public service/utility commissions, utility boards or similar entities. |

Note: This table is not comprehensive of all financing mechanisms.

Green banks leverage public and private capital to invest in innovative and sustainable projects, which may be overlooked by traditional financial institutions, to accelerate the transition to clean energy and reduce emissions.

Funding can be paired with financing for vehicles and their charging infrastructure to extend public dollars further, bringing the benefits of electric school buses to more communities.

Why Finance?

- Monetize future maintenance and fuel savings and apply these towards the initial capital investments that electric buses require. Due to low electricity prices and fewer maintenance needs, it is estimated electric school buses can reduce operational costs by more than $100,000 over their lifetime, compared to their diesel counterpart, using national averages of costs. These savings can be financed and allow districts to restructure school bus electrification costs so that they more closely resemble the operational budget and cash flow characteristics of incumbent diesel vehicles and can enable districts to make the investments necessary to realize cost-effective projects.

- Prioritize funding for disadvantaged communities. Extending public dollars with financing allows policymakers to direct grant and other types of funding toward communities most in need. School districts in underserved communities may have poor credit or lack capacity to issue public bonds to raise capital and so might face higher interest rates that would result in higher overall project costs.

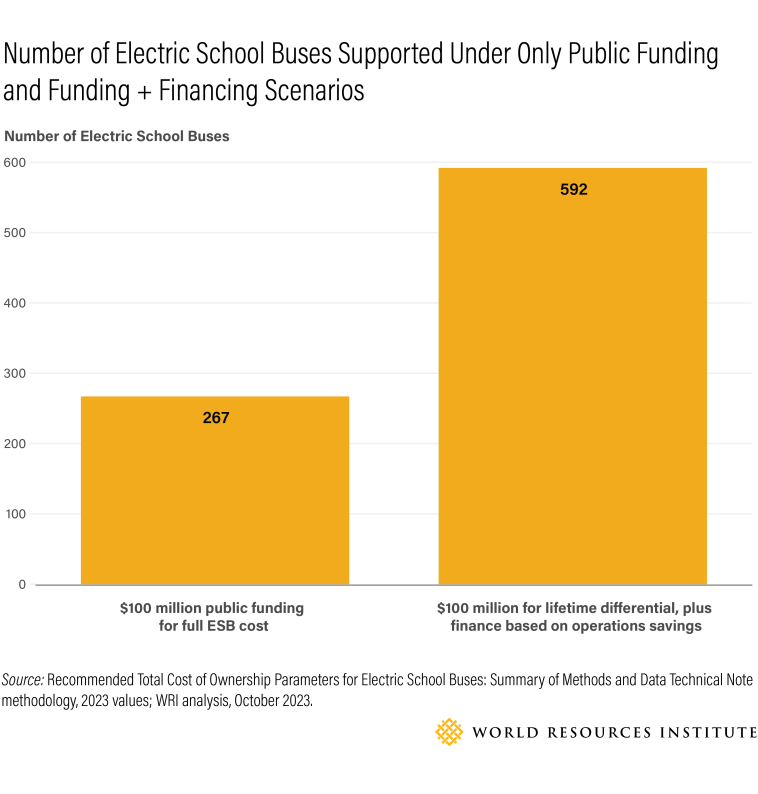

- Scale the number of electric school buses on the road. Leveraging financing with public funding can significantly increase the number of buses procured, thus scaling electric adoption more quickly. To illustrate this concept, Figure 2 below displays two scenarios.

Upfront premium is the price difference of an electric school bus compared to its internal combustion counterpart.

Lifetime premium is the difference of the total cost of owning (TCO) an electric school bus compared to its internal combustion counterpart. This includes cumulative cost differences in upfront cost, fuel, operations and maintenance costs over its lifetime.

- In the first scenario, “Funding only,” public funding covers the full cost of an electric school bus, or $375,000 per bus for the purpose of this example. In this scenario, a $100 million public funding investment results in 267 electric school buses.

- In the “Funding + Finance” scenario, the upfront cost of an electric school bus is covered by a mix of public funding, public financing, and schools' transportation budgets. In this scenario, public funding provides school districts $169,000 per bus, which represents the lifetime premium and eligible tax credits. Once the lifetime premium of an ESB is covered, the total cost of ownership is the same as that of a diesel bus. Then, government agencies can capitalize on operational savings (estimated to be $157,000 over the lifetime of the bus) by providing $157,000 in public finance. These mechanisms cover the upfront price difference between an electric school bus and its internal combustion counterpart, therefore, reducing the amount of public funding required per ESB and increasing the number of ESBs purchased with the same $100 million investment to 592 buses.

How policymakers can complement funding programs with financing to maximize impact

Policymakers can consider the following recommendations to extend the impact of public funding investments and prioritize underserved communities in the transition to ESBs.

- Public funding programs, in which funds for electric school buses do not need to be repaid, should be designed to prioritize underserved communities. Because environmental justice and other underserved communities may have higher barriers to accessing loans or face higher interest rates, 50% of public funding should be dedicated to EJ and other underserved communities. This would mirror California’s Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Program that aims to provide at least 50% of funding to disadvantaged communities. One could envision even higher levels of funding for underserved communities with accompanying financing support for more well-resourced communities.

- When designing programs to incentivize the transition to electric school buses, policymakers should complement public funding with financing to extend the reach of each publicly invested dollar and maximize air quality and health benefits. This mirrors the example mentioned above (Figure 2), in which pairing funding with financing increases the overall number of electric school buses funded. While there are no electric school bus programs that include financing currently, the USDA Communities Facilities Program can be a point of reference. The program provides grants, direct loans and loan guarantees to eligible recipients to build key community infrastructure in rural areas. It is important to note that the proportion of funding and finance will vary by the criteria and project characteristics. Nonetheless, it is critical for policymakers to evaluate different program structures that provide a variety of options to school districts from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds.

- Expand opportunities for public financing by making ESBs eligible for low or zero interest financing in government public lending programs and green banks. Upcoming grantees of EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund competition are well positioned to consider including electric school buses within their portfolio of lending programs. Green banks can leverage public and private capital to provide low-cost loans to school districts, whose creditworthiness may be classified as riskier than traditional borrowers depending on the repayment timeline, revenue streams or debt limits.

- Expand access to credit enhancement tools for school electrification projects to reduce financing costs. These mechanisms, often used for bonds, provide a guarantee of repayment in the event schools face financial difficulties. Many states have permanent funds, state aid intercepts or guaranty programs that can enhance credit ratings for school districts and lower their interest rates for capital projects. Additionally, due to their quasi-public structure, green banks can also provide credit enhancement mechanisms and financial tools to reduce the risk perceived by traditional financial institutions.

- Policies and programs supporting the adoption of ESBs should consider funds to be utilized on the services offered by transportation and infrastructure companies, such as OEM leasing, CaaS, IaaS and TaaS firms, so districts, including those that do not have access to the upfront capital needed to electrify, have a range of electrification pathways.

- Work with state utility commissions, regulatory boards and regulators to incentivize investor-owned-utilities, rural electric cooperative, or municipal utilities to offer inclusive utility investment programs to school districts in their service area. Inclusive utility investments on electric buses can cover charging infrastructure (charger and required infrastructure) and the battery of the bus. These specific inclusive utility investments are approved by commissions (in the case of IOUs) or boards (in the case of rural coops) with a cost recovery tariff that is time bound and based on the savings produced by the new technology. While the cost recovery period is underway, the assets belong to the utility, but once they are paid off, the assets belong to the customer. All benefits from the assets (e.g., V2G services from the battery) during the cost recovery should be used to reduce the cost of the tariff and make it more affordable.

Thank you to our external reviewers, Victor Rojas (Sustainable Capital Advisors) and Molly McGee-Hewitt (National Association for Pupil Transportation). Special thanks to Margarita Parra and Lexie Lyng of Clean Energy Works for their thought partnership and invaluable collaboration on this work.