How to Find the Right Electric School Bus Business Model for Your District

An Electrifying Decision: Which Electric School Bus Business Model is Right for Your District?

The electrification of school buses presents districts with the opportunity to assess their existing arrangement of roles, responsibilities and financial obligations – in other words, their business models – and consider an array of new options that have emerged in the school transportation market.

Historically, United States school bus business models have been relatively static, with 60% of school districts directly owning or leasing and operating fleets, while the other 40% of districts contracting with private operators. Complementing these options, interest in fleet electrification has prompted the emergence of business models that address distinctly the unique challenges and opportunities associated with electric school buses (ESBs).

Business model (noun):

The arrangement of roles and responsibilities for achieving a business objective; this can include asset ownership, revenue sources, details of financing and assignment of risk. In the case of school transportation, this covers district decisions like whether to own, lease or contract out for vehicles and how operator and maintenance functions are staffed.

Why Electrification Poses an Opportunity to (re)Think School Transportation Business Models

ESB costs are incurred differently than the costs of traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) buses: ESBs have much higher upfront capital costs and much lower operating costs, while the opposite is true for diesel buses. This means that over the lifetime of the bus, an electric bus might have lower total costs than a diesel bus, despite having a higher initial cost.

For school officials, this difference in capital and operating expenses can be meaningful. Securing funding for capital expenses is generally more challenging than for operating expenses, as they involve higher, one-time amounts that may call for approval by voters (if tied to a bond, for instance) or a school board, compared to small amounts spread out over time. This is where financing — and the potential role for new business models — comes in. By financing the purchase of an ESB, school districts can use the operational savings accrued over the lifetime of the bus to help pay for the higher capital expense over time.

The transition to ESBs presents novel risks for school districts, including the need to implement sophisticated energy management systems and navigate technologies that are maturing and changing. It also poses new opportunities such as revenue generation from providing battery capacity to the electric grid during times of peak demand and increased site or community resilience through ESB integration into emergency response plans. Additionally, as discussed below, electrification introduces new assets, roles and responsibilities beyond those associated with ICE buses.

The Real Cost of Electric School Buses is Lower Than You May Think

Although electric school buses have higher upfront costs today than their fossil fuel counterparts, costs are projected to decline due to decreasing battery costs and increasing economies of scale in component markets. Once purchased, the cost of operating and maintaining an electric school is thousands of dollars a year less, helping lower the total cost of ownership (TCO) – the combination of the initial purchase cost and costs over time. Electric school buses are projected to reach TCO parity with diesel buses, including accounting for charging infrastructure, by 2029, and initial price parity by 2033. As TCO drops below that of diesel buses, electric school buses will produce net savings for school districts. This is all expected to happen in a relatively short amount of time. And, where there are incentives available, such as through the federal Clean School Bus Program or various state or utility programs, many electric school buses can already achieve TCO parity today.

The Challenges and Opportunities of Electrification Are Greater for Underserved Communities

Underserved communities disproportionately bear the harms of air pollution and the impacts of climate change. This is driven in part by the existing fossil fuel transportation system and production processes as well as the unjust lending, transit, housing and zoning policies that have concentrated communities of color closer to highways and other pollution sources. In addition, low-income students and students from Black households are more likely to ride the bus to school, making them more likely to be exposed to diesel exhaust.

While it is essential to transition to clean transportation options to mitigate these burdens, underserved communities may face exacerbated challenges when making this transition. Access to capital is essential to make necessary investments in clean vehicles and infrastructure, but underserved communities often face higher costs to borrow this capital and have smaller tax bases from which capital can be raised. School district staff may also lack resources and capacity to undertake the project management required to carry an electrification project to fruition. Further, underserved communities may have underinvested local electric distribution infrastructure, which means that pursuing electrification may be more likely to trigger infrastructure upgrades to support ESBs that increase overall project costs.

Because of disproportionately higher levels of ambient air pollution and higher levels of school bus ridership, underserved communities are expected to realize outsized benefits from the transition to electric transportation. Localities bearing the highest air pollution burden from transportation fuels will see the largest air quality improvements from these electrification transitions, resulting in greater local health benefits. Likewise, the operational savings and revenue generation opportunities posed by ESBs will go further to support district priorities in places where resources are scarcer. Pursuing transportation electrification can jump-start workforce development and training that ensures a community is included in the green economy of tomorrow.

Selecting the Right Business Model for Your District

With so much on the line, how should districts navigate the decision around selecting a business model that works best for them? Schools are already on the lookout for available funds (local, state, federal, utility). By considering complementary financing and new business models, they can leverage these funding resources for greater impact. To understand business model options, districts need to identify the assets (buses and infrastructure) and associated roles of bus electrification; consider ownership options and stakeholders; and weigh their appetite to absorb risk and make the most of opportunities.

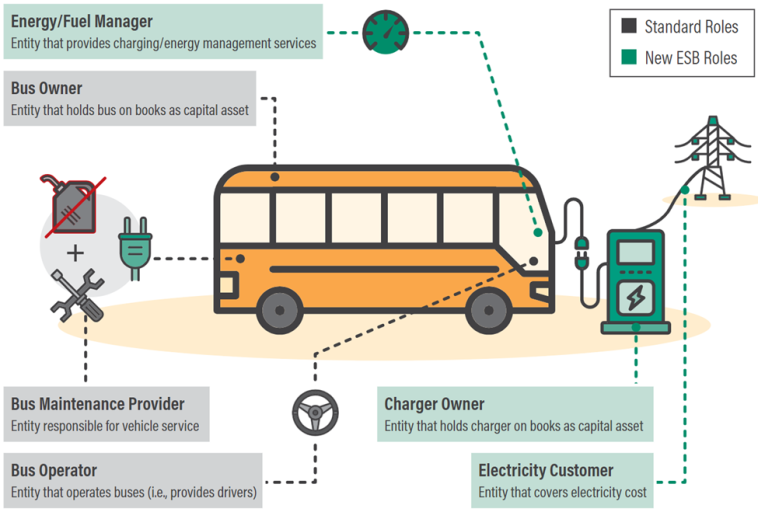

Six key roles are illustrated in Figure 1 and defined below.

- Bus owner: the entity that holds the bus on its books as a capital asset. Note that the owner of the bus, such as the district, may be a separate entity from the owner of the battery, such as a utility.

- Charger owner: the entity that holds the charger on its books as a capital asset. Note that an operational charger often requires additional infrastructure (e.g. conduit, panel, etc.) on the customer’s side of the meter. The owner of the customer-side infrastructure may be a distinct entity from the owner of the charger, such as a utility. Likewise, the entity responsible for charger maintenance may be a distinct entity from the owner of the charger.

- Bus operator: the entity that operates the buses – providing drivers and planning routes.

- Bus maintenance provider: the entity responsible for scheduled and unscheduled service of the vehicles to enable optimal performance and extend their lifetimes.

- Energy/fuel manager: the entity that provides charging and energy management services including monitoring state of charge, scheduling vehicle charging needs and managing load. Where applicable, this may also include sending and receiving grid signals and providing vehicle-to-everything (V2X) energy flows. Note that some chargers’ hardware providers include energy management software as part of their package.

- Electricity customer: the entity that pays for electricity consumed by the chargers; note that electricity service will be provided by the utility, but contractual arrangements may assign electricity costs to an entity other than the account holder, depending upon the business model pursued.

Contracts (e.g. ownership, lease agreements, service agreements, master services agreements or energy savings performance contracts) formally assign responsibilities, duties, obligations and benefits across the roles and elements of each business model. Technical advisors, such as a third-party review entity, can be hired to help fill any knowledge gaps and can review contracts to ensure that all liabilities are assigned appropriately when there are multiple partners involved in a project.

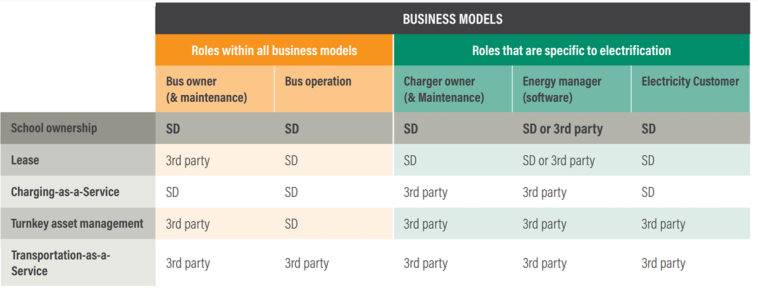

Table 1 Below presents several types of business models emerging for school bus electrification and the parties responsible for different roles under each model.

There are various entities that could fulfill each role, with potential benefits and tradeoffs to each approach. The term “3rd party” refers to any entity that is not a school district, including original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), school bus contractors, private energy companies, a local electric utility, etc. Through a systematic review of its priorities, strengths and resources, a district can determine the best business model to carry it through the electrification transition. To get a more in-depth look at the benefits and considerations of a school district or 3rd party filling each role, please review the Electric School Bus Business Models Guide.

The possibilities are endless…

The Taxonomy presented in Table 1 does not encompass all potential combinations of roles or business model variations for the provision of electric school transportation. Taking cues from the transit and energy efficiency sectors, districts can explore battery leasing like Valley Regional Transit, or inclusive utility investments for on-bill financing of electrification as the DTE Electric Company has proposed under the guidance of Clean Energy Works.

Here are examples of distinct business model arrangements that five school districts have undertaken in their processes to electrify their buses:

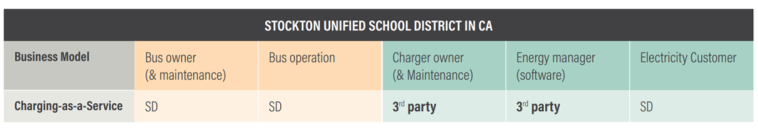

- Stockton Unified School District (SUSD) in California – For SUSD, bus procurement, bus ownership, bus maintenance and operation, as well as the electricity costs are the responsibility of the school district. The district has contracted out charger ownership and maintenance and energy management to a Charging-as-a-Service company (The Mobility House).

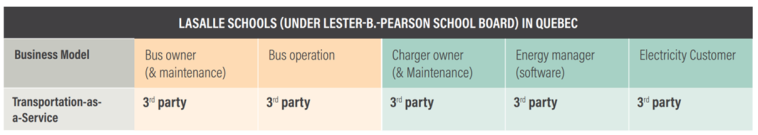

- Select schools in Lasalle, Quebec (under Lester-B.-Pearson School Board) – For schools in Lasalle that contract with Transco, a First Student subsidiary, all roles in the business model are the responsibility of the 3rd party, a Transportation-as-a-Service approach.

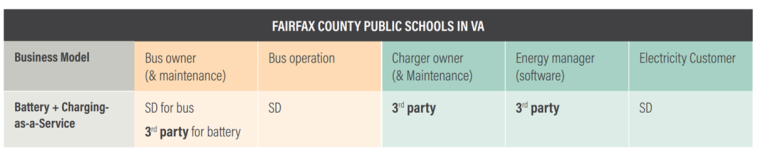

- Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) in Virginia – For FCPS, bus ownership, bus maintenance, bus operation and electricity costs are the responsibility of the school district. A third party, the local utility (Dominion Energy), covered bus procurement, battery ownership, charger infrastructure, charger ownership, charger maintenance and energy management. Battery ownership allows the utility to utilize V2G technology if they wish. This model can be described as Battery + Charging-as-a-Service. Other school districts and utilities are following suit, such as Cherokee Central Schools (CCS) and Duke Energy in North Carolina.

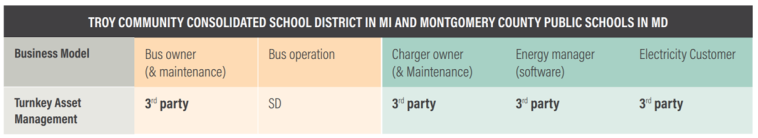

- Troy Community Consolidated School District (TCCSD) in Illinois and Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland (MCPS) – TCCSD and MCPS determined that turnkey asset management was the model that best fit their districts. Their third-party contractors, Levo Mobility and Highland Electric Fleets, respectively, are responsible for all roles except bus operation.

Additional resources:

- WRI has developed a resource for school districts to identify the appropriate business model to support electrification of school transportation in their district. Please visit our Electric School Bus Business Models Guide for further discussion of benefits and considerations, and school districts can weigh in assessing business model options.

- WRI has compiled a list of firms that offer services across the landscape of ESB business models, including their contact information. Please visit our School Bus Electric-as-a-Service (EaaS) directory to identify and connect with those firms that complement whichever business model is appropriate for your district. Please note the information in this database is sourced from firm websites and/or staff, and inclusion of a firm in this list does not constitute endorsement by WRI or the ESB Initiative.

- Refer to the U.S. Department of Energy Vehicle Technologies Office’s Electric School Bus Education Resources.

- The American Association of School Administrators has prepared this School Budgets 101 brief.

- On budgeting for school bus fleets specifically, look to this 2015 article from SchoolBusFleet.com, “10 Keys to Success in School Transportation Budgeting.”

- Released in June 2022 in Automotive Fleet, “How Fleet Manager’s Roles Evolve with EVs.”

WRI may provide general knowledge for educational and informational purposes only. Such information or materials do not constitute and are not intended to provide legal, accounting or tax advice and should not be relied upon in that respect. We recommend you consult your attorney, accountant and/or financial advisor to answer any financial, tax or legal questions. If you rely on any information provided by WRI, you do so at your own risk.