Next Stop, Access! Working Paper: HTML Accessible Version

Next Stop, Access! An Exploratory Paper on Disability Rights and Justice Throughout the Transition to Electric School Buses

Authors: Justice Shorter, Valerie Novack, Alyssa Curran

Table of contents

Before you read

Next Stop, Access! An exploratory paper on disability rights and justice throughout the transition to electric school buses

Dedication

Highlights

Executive summary

About this working paper

Key findings

Recommendations

Introduction

Background

Disability justice (DJ) and environmental justice (EJ)

Legal context

Methodology

Research approach

Research limitations

Research findings

Inclusion, barriers, and improvements

Key findings

Intersectional, environmental, and infrastructural considerations

Key findings

Current transportation access and technology concerns

Key findings

Educational impacts

Key findings

Improving accessibility

Key findings

New opportunities and multipurpose uses

Key findings

Discussion

Recommendations

Consult and include youth with disabilities during transition efforts.

Avoid replicating the inaccessibility problems of current diesel school bus fleets and expand the accessibility of school buses in the transition.

Conclusion

Next stop, access! Before you read

This document is a preread companion to the Electric School Bus Initiative and SeededGround working paper “Next stop, access! An exploratory paper on disability rights and justice throughout the transition to electric school buses.” This preread provides readers further background on the disability and environmental justice research lens used throughout the working paper and definitions for key concepts referenced in the research.

Where we ground: Disability justice and environmental justice

About disability justice

The disability justice (DJ) framework was established by a group of queer and disabled activists of color connected through Sins Invalid, a performing arts organization. In 2005, Stacey Park Milburn, Pattie Berne, and Mia Mingus, alongside many others, first defined DJ in response to a lack of equity and access within the disability rights movement. DJ offered a principled framework and intentional space and safety for people experiencing multiple levels of oppression. Unlike the independence and compliance foci of a rights-based framework, DJ requires collective action and a focus on the whole experience of individuals, with efforts led by those most impacted (Sins Invalid 2015).

About environmental justice

Like DJ, the environmental justice (EJ) framework is rooted in communities of color. Shaped by extraordinary advocates such as Dr. Robert Bullard and Hazel Johnson, EJ focuses on addressing systemic inequities that result in disproportionate environmental harm on marginalized communities. The EJ movement actively seeks to change the environmental, economic, political, and social conditions that directly and indirectly harm communities. Delegates of the 1991 First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, held in Washington, DC, rooted EJ in 17 principled commitments. The EJ framework offers guidance on how to acknowledge, analyze, and rectify the ways the environment impacts public, physical, mental, and spiritual health and well-being (First National 1991).

Key definitions

Accessible school bus

Commonly defined as a bus equipped with a power wheelchair lift (often located at the rear or center of the vehicle), or a bus with a retractable entryway ramp (often located at the front of the vehicle). This also includes designated wheelchair securement areas in addition to wheelchair tie-downs to prevent movement during transit. A bus with these features offers access for students and adults with physical disabilities (US Access Board 2016).

- For the purposes of the working paper, accessibility is defined as something far broader than simple wheelchair access. This definition includes any designs and devices that allow students with diverse disabilities to reliably ride on school buses with ease, comfort, and safety. Accessibility is thus achieved through recognition of individual needs, adaptable approaches that support diverse disabled bodies and minds, dependable equipment, and trained bus operators and bus monitors and aides.

- Furthermore, the working paper seeks to stretch the possibilities of how accessible school bus features are defined. For instance, research participants provided several innovative and insightful ideas for how access can evolve alongside electric vehicles. Participants shared that less commonly referenced, but equally as important, accessibility features can include adaptable seats and seatbelts, storage spaces, temperature regulation, air ventilation, audiovisual communications, and reduced stimulation (noise, vibration, etc.). Their suggestions are further outlined throughout the working paper’s “Key findings” section.

Disability justice

A framework that values diversity in all forms of disability and promotes access, self-determination, and interdependence. It recognizes the complexities of multiple marginalized disabled people and aims to be holistic in recognizing these complexities. The 10 principles of disability justice include the following:

- Intersectionality

- Leadership of those most impacted

- Anti-capitalist politica

- Commitment to cross-movement organizing

- Recognizing wholeness

- Sustainability

- Commitment to cross-disability solidarity

- Interdependence

- Collective access

- Collective liberation (Sins Invalid 2015)

Disability rights

Federal, state, Tribal, and local laws that provide protections for people with disabilities include the following three major pieces of legislation (Southwest ADA Center 2018):

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in several areas, including employment, transportation, public accommodations, communications, and access to state and local government programs and services (US Access Board n.d.).

- Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance, or under any program conducted by any executive agency or by the US Postal Service (OCR 2023).

- The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is a law that makes available a free appropriate public education to eligible children with disabilities and ensures special education and related services to those children (OSERS n.d.).

Environmental justice

The principle of ensuring equitable treatment and active engagement of all individuals, irrespective of their race, color, national origin, or income, in the creation, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies, while securing equal access to environmental safeguards and advantages in their communities. Environmental justice is characterized by 17 principles:

- Environmental justice affirms the sacredness of Mother Earth, ecological unity and the interdependence of all species, and the right to be free from ecological destruction.

- Environmental justice demands that public policy be based on mutual respect and justice for all peoples, free from any form of discrimination or bias.

- Environmental justice mandates the right to ethical, balanced, and responsible uses of land and renewable resources in the interest of a sustainable planet for humans and other living things.

- Environmental justice calls for universal protection from nuclear testing, extraction, production, and disposal of toxic/hazardous wastes and poisons and nuclear testing that threaten the fundamental right to clean air, land, water, and food.

- Environmental justice affirms the fundamental right to political, economic, cultural, and environmental self-determination of all peoples.

- Environmental justice demands the cessation of the production of all toxins, hazardous wastes, and radioactive materials, and that all past and current producers be held strictly accountable to the people for detoxification and the containment at the point of production.

- Environmental justice demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making including needs assessment, planning, implementation, enforcement, and evaluation.

- Environmental justice affirms the right of all workers to a safe and healthy work environment, without being forced to choose between an unsafe livelihood and unemployment. It also affirms the right of those who work at home to be free from environmental hazards.

- Environmental justice protects the right of victims of environmental injustice to receive full compensation and reparations for damages as well as quality health care.

- Environmental justice considers governmental acts of environmental injustice a violation of international law, the Universal Declaration On Human Rights, and the United Nations Convention on Genocide.

- Environmental justice must recognize a special legal and natural relationship of Native Peoples to the U.S. government through treaties, agreements, compacts, and covenants affirming sovereignty and self-determination.

- Environmental justice affirms the need for urban and rural ecological policies to clean up and rebuild our cities and rural areas in balance with nature, honoring the cultural integrity of all our communities, and providing fair access for all to the full range of resources.

- Environmental justice calls for the strict enforcement of principles of informed consent, and a halt to the testing of experimental reproductive and medical procedures and vaccinations on people of color.

- Environmental justice opposes the destructive operations of multi-national corporations.

- Environmental justice opposes military occupation, repression, and exploitation of lands, peoples and cultures, and other life forms.

- Environmental justice calls for the education of present and future generations which emphasizes social and environmental issues, based on our experience and an appreciation of our diverse cultural perspectives.

- Environmental justice requires that we, as individuals, make personal and consumer choices to consume as little of Mother Earth's resources and to produce as little waste as possible; and make the conscious decision to challenge and reprioritize our lifestyles to insure the health of the natural world for present and future generations. (First National 1991)

Intersectionality

A term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality illuminates how various social categorizations such as gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, and class intersect within an individual or group, resulting in interconnected systems of discrimination and disadvantage. It stresses that these inequalities are mutually reinforcing, demanding a simultaneous examination and remedy to prevent one form of discrimination from amplifying another (Crenshaw 1989).

Person-first language vs. Identity-first language

Person-first language emphasizes the person before their disability, such as phrases like “a person who is blind” or “individuals with spinal cord injuries.” Identity-first language places the disability at the forefront, such as phrases like "a deaf person" or "an autistic child." The choice between person-first and identity-first language should be based on personal preference, and when uncertain, it is best to ask the individual for their preference directly.

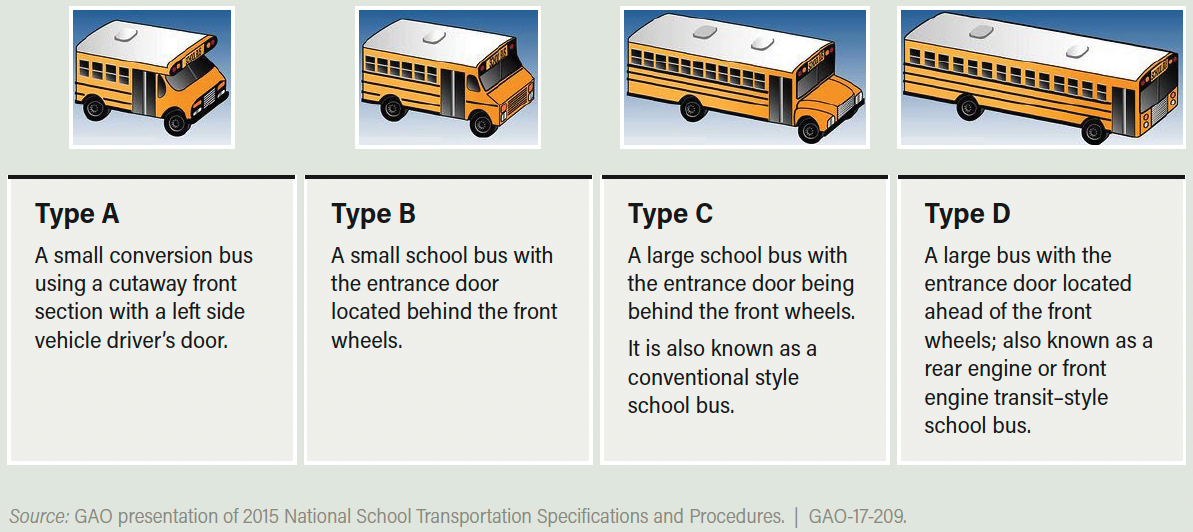

School bus types

The four primary types of school buses are categorized based on size and design. The new buses referred to in the transition have electric power sources instead of diesel and other internal combustion engine vehicles.

- Type A: Type A buses are the smallest school buses on the road, designed to carry 10–30 passengers. Type A school buses play an important role in special education student transportation. One reason for this is that special education routes are often door-to-door and pick up a small group of students, making a larger bus unnecessary. Type A buses most commonly run on gasoline and are built on a Ford or General Motors cutaway-cab chassis platform. This design is akin to a big pickup truck without a bed with a school bus body integrated on the back. Currently, nine available electric school bus (ESB) Type A models have the capacity to be equipped with ADA lifts.

- Type B: These buses are no longer manufactured. No Type B buses are slated to be incorporated into the electric school bus transition. However, for awareness purposes, a “Type B school bus” is a conversion or body constructed and installed on a van or front-section vehicle chassis, or stripped chassis, with a gross vehicle weight rating of more than 10,000 pounds, designed for carrying more than 10 people. There are very few Type B buses on the road today.

- Type C: Type C buses are the classic conventional school buses that most people think of and account for about 70% of school buses in the United States. Type C buses have a long body and are designed to carry between 36 to 77 passengers. Type C buses have a distinctive hood or “nose” on the front of the vehicle, designed to house the internal combustion engine (this houses different components on an ESB). The door to this type of bus is always located behind the front wheels. Type C buses usually run on diesel, but quite a few propane and compressed natural gas (CNG) models are in circulation as well. All currently available Type C ESBs have the capacity to be equipped with ADA lifts.

- Type D: Type D buses are the largest school bus type, carrying up to 90 passengers. Type Ds account for about 20% of the school bus market. Type D buses are “transit style,” with the front of the bus being flat. The engine can be mounted in the front, beneath the driver’s seat, or in the rear of the bus. The door to the bus is located ahead of the front wheels. Type D buses usually have undercarriage storage and for this reason are commonly used for school field trips and sports teams. Type D buses can be equipped with wheelchair lifts, but this is less common. Type Ds usually run on diesel, sometimes on CNG. All currently available Type D ESBs have the capacity to be equipped with ADA lifts. (Huntington et al. 2023)

Students with disabilities/disabled students

Multiple assessment factors are used to determine a student’s disability. However, many students of color, students in low-income areas, and immigrant families face inequitable access to required diagnostic testing and medical documentation. These metrics also do not account for alternative ways of validating “embodied knowledge” concerning body-mind awareness, family histories, and lived experiences. For the purposes of this working paper, the phrases “students with disabilities,” “disabled students,” “adults with disabilities,” and “disabled adults” will refer to but are not limited to people with the following conditions:

- Physical or mobility disabilities

- Cognitive or intellectual disabilities

- Hearing loss or deafness

- Vision loss or blindness

- Deaf-blindness

- Speech or communication disabilities

- Learning disabilities

- Mental health or psychiatric disabilities

- Traumatic brain injuries

- Autism

- Chronic illnesses

Universal design

Also referred to as inclusive design, accessible design, or accessibility, universal design refers to the design and manufacturing of vehicles (school buses) with specifications that accommodate the broadest spectrum of potential users. This approach emphasizes the inclusion of disabled students by integrating accessible features into the design from the outset, rather than adding them as modifications.

According to the American Public Transportation Association, “Universal design is the design of equipment, environments and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaption or specialized design regardless of gender, ethnicity, health, size, ability, disability or other factors that may be pertinent. Universal design is the implementation of a process that improves the quality of life and greatly improves independence by enabling and empowering a general, yet diverse, world population to achieve optimal human performance, health and wellness through equal access to all facilities and social participation” (APTA 2020).

Note: a As written in the original.

Thank you for reading “Next stop access! Before you read.” Please continue to the working paper, “Next stop, access! An exploratory paper on disability rights and justice throughout the transition to electric school buses,” which can be accessed through DOI at https://doi.org/10.46830/wriwp.23.00046.

References

APTA (American Public Transportation Association). 2020. “Transit Universal Design Guidelines: Principles and Best Practices for Implementing Universal Design in Transit.” July 28. APTA-SUDS-UD-GL-010-20.pdf.

Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum, no. 1. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf.

First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. 1991. “The Principles of Environmental Justice.” October 27. https://www.ejnet.org/ej/principles.pdf.

Huntington, A., J. Wang, P. Burgoyne-Allen, E. Werthmann, and E. Jackson. 2023. “Electric School Bus U.S. Market Study and Buyer’s Guide: A Resource for School Bus Operators Pursuing Fleet Electrification.” World Resources Institute, July. https://doi.org/10.46830/wriib.21.00135.v2.

OCR. 2023. “Protecting Students with Disabilities: Frequently Asked Questions about Section 504 and the Education of Children with Disabilities.” US Department of Education, July 18. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/504faq.html#introduction.

OSERS. n.d. “Individuals with Disabilities Education Act: Statute and Regulations.” US Department of Education. https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statuteregulations/.

Sins Invalid. 2015. “10 Principles of Disability Justice.” September 17. https://www.sinsinvalid.org/blog/10-principles-of-disability-justice.

Southwest ADA Center. 2018. “Disability Rights Laws in Public Primary and Secondary Education: How Do They Relate?” ADA National Network. https://adata.org/factsheet/disability-rights-laws-public-primary-and-secondary-education-how-do-they-relate.

Next stop, access! An exploratory paper on disability rights and justice throughout the transition to electric school buses

Dedication

This working paper is dedicated to students and youth with disabilities. May each reader receive and reflect on this research in loving memory of all the disabled lives lost because of inaccessible and unsafe transit systems. May this work inform and ignite our collective imaginings of more equitable transportation. May it contribute to ongoing initiatives devoted to the creation of safety, dignity, and belonging of every student with a disability. We hope the following pages propel policies and practices toward advocacy efforts that prioritize the leadership and needs of diverse students with disabilities throughout all phases of the transition to electric school buses.

Highlights

- This Electric School Bus (ESB) Initiative working paper gathers and analyzes literature and qualitative responses from students, youth, parents, and professionals from stakeholder groups across the ESB transition.

- Student and youth participants in the study described how the transition to ESBs cannot be fully realized without the meaningful inclusion of students with disabilities and their families throughout all phases of planning, implementation, and future adjustments of school transportation programs. They also emphasized the need for all school buses to be accessible.

- The transition to ESBs has the potential to either expand transportation equity for people with disabilities or replicate preexisting transportation barriers, which currently offer narrow accommodation options for diverse bodies and minds, pose safety challenges, and restrict mobility access.

- Key recommendations include consulting with disabled youth during transition efforts, prioritizing accessibility measures, addressing design problems, and strengthening accountability measures for legal compliance with disability laws.

- This study also identified several key gaps in data that would help provide a more complete picture of school transportation access for disabled students.

Executive summary

About this working paper

This working paper is powered by diverse perspectives and priorities from across communities of disability, transportation, and environmental justice advocates. With a focus on disability rights and justice, this paper examines the ways students and adults with disabilities are impacted by the electrification of school buses and shares their recommendations for designing a transition that achieves equity and accessibility. Critical research areas posed in this paper include but are not limited to the following:

- Disability-specific challenges and benefits of electrifying school bus fleets

- Availability and accessibility of school bus design features

- Health implications of electrifying school bus fleets

- Multipurpose school bus usage outside of standard school activities

- Geographic factors

Moreover, this paper strives to acknowledge past and present-day harms caused by intersectional transportation inequities, center those who could be most impacted, and amplify solutions that steer us toward a more equitable future. It finds that the transition to ESBs must be driven by equity and accessibility.

Key findings

Researchers gathered data and perspectives from 24 participants using surveys, interviews, facilitated discussions, and public records reviews. Participants included students and other youth (9), advocates (3), school bus manufacturers and dealers (2), government officials (2), school district staff (3), attorneys (3), a researcher (1), and a transit union representative (1) (Appendix A).

Research participants conveyed challenges related to infrastructure, the environment, and accessibility that pervade present-day school transit programs:

- Unreliable school bus ramps and lifts

- Sensory overstimulation from diesel buses

- Safety risks caused by untrained bus drivers and monitors

- Inconsistent compliance with state and federal disability laws

- Unsafe or absent infrastructure like narrow sidewalks, a lack of curb cuts, or obstructed paths of travel

- Disproportionate climate impacts on people with disabilities, and particularly people of color with disabilities, such as impacts on health, infrastructure, and disaster recovery

- Inadequate resource allocation for schools to support students with disabilities

- Intersectional issues impacting disadvantaged students, such as parent teacher associations that don’t accommodate working and disabled parents and the higher prevalence of air pollution in low-resourced communities

Recommendations

Research participants provided recommendations for stakeholders and school districts that could rectify rather than repeat inequities impacting disabled students and their families.

- Consult and include youth with disabilities during transition efforts.

- Proactively involve students with diverse disabilities and their families in decision making during all phases of ESB transition projects.

- Avoid replicating the same inaccessibility problems present on current diesel school bus fleets.

- Prioritize the deployment of buses that serve students with disabilities along with other underserved communities.

- Every bus procured should have accessibility features, such as a wheelchair ramp or lift, so all students can always have transportation access. Every bus should also include accessibility features that go beyond current accessibility standards.

- Identify and address the intersectional, environmental, and infrastructural challenges of underresourced communities in the transition.

- Address current design and maintenance problems. Specifically, malfunctioning wheelchair lifts are unreliable and unsafe for students, drivers, and monitors. Design improvements can also include announcement or noise systems to address the hazards quieter ESBs pose to people with vision disabilities.

- Make universal design an industry standard.

- Reassess the current system of policy guidance and accountability to ensure that school districts and manufacturers comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

- Expand the accessibility of school buses in the transition.

- Incorporate multipurpose uses of ESBs for students with disabilities.

- Use technology to improve rider comfort, external communication, and safety on the bus.

- Explore additional community-serving and resilience uses of ESBs.

Introduction

In collaboration with partners and communities, the Electric School Bus (ESB) Initiative of World Resources Institute (WRI) aims to build unstoppable momentum toward an equitable transition of the entire US school bus fleet from primarily diesel-burning fuel to electric, bringing health, climate, and economic benefits to children and families across the country and normalizing electric mobility for an entire generation.

Across the nation, school districts are increasingly integrating ESBs into their school transportation systems. This shift has been supported by federal and state governmental funding, notably the $5 billion federal investment to initiate the switch to electric and low-emission buses through the Clean School Bus Program (CSBP) administered by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (White House 2022). As of April 2024, ESBs had commitments for over 12,000 buses across 49 states and several territories and Tribal nations, which is a nearly 10-fold increase in adoption since the initiative first published its dataset in August 2021, when there were just over 1,000 ESBs committed (Freehafer and Lazer 2024).[i] Some government funding programs also include equity provisions, such as prioritizing funding for underserved communities, and, more recently (2023), additional funding for accessible features. The ESB Initiative is tracking the efficacy of these policies.

This working paper is part of the initiative’s efforts to develop a foundation of research into the necessary centrality of equity in the US ESB transition. It builds on the “Equity Framework to Guide the Electric School Bus Initiative” (Moses and Brown 2022) and the “Electric School Bus Initiative Advocacy Stakeholder Analysis: A Baseline Report” (Brown and Curran 2023) (hereafter referred to as “the advocacy stakeholder analysis”). From the advocacy stakeholder analysis outcomes, the ESB Initiative concluded that further research was required on disability rights and disability justice concerning the equitable transition to ESBs, resulting in this working paper.

Central to an equitable transition, students and adults with disabilities must be among the prioritized communities to realize the benefits of clean transportation. Students with disabilities using transportation services experience several inequities related to the accessibility of school bus fleets. They also continue to experience segregation due to separate special education buses and a lack of fully accessible school bus fleets. Most school buses in a fleet do not include commonly recognized accessibility features such as a power wheelchair lift or retractable entryway ramp, which offer access to students and adults with physical disabilities.

School buses that do include these features are often designated as special education buses, separating disabled students from their classmates. In addition, students have diverse disabilities ranging from physical to cognitive to speech to chronic illness, which broadens our common definition of accessibility. Accessibility features can also include adaptable seats and seatbelts, storage spaces, temperature regulation, air ventilation, audiovisual communications, and reduced stimulation (i.e., noise, vibration).

Students with disabilities from underserved racial or ethnic, gender, sexual orientation, income, or geographic groups also experience inequities due to overlapping systems of discrimination and disadvantage, also defined as “intersectionality” (Crenshaw 1989). The US education system grapples with resource disparities and disparities in outcomes among students (often referred to as the “achievement gap”), which are seen along racial or ethnic, income, geographic, and disability lines (Bradley 2022; Porter n.d.). One study estimates that without changes to determining factors such as inequitable resource allocation, achieving educational parity between white students and students of color could take up to 160 years (Bryant et al. 2023).

The legacies of resource inequities in US schools are visible in the transition to ESBs. In 2021, Maryland’s Montgomery County Public Schools (MCPS) Board of Education made a commitment to electrify its fleet over four years. However, in August 2022, MCPS announced that due to supply chain shortages, the school district would still purchase diesel school buses to serve students in its special education program (Ramirez 2022). The Board of Education officially approved the procurement of 90 diesel buses to serve special education students in October 2023. In response, students, parents, and environmental activists rallied to protest the school board’s decision, asking for “due diligence and [demanding that the district] be proactive when problems with electric or with transportation arise,” rather than going back on its promise to provide clean transportation (Griffin 2023). Montgomery County is majority Black, Indigenous, and People of Color, and students with disabilities from underserved racial, ethnic, or other groups face overlapping systems of inequitable resource allocation (Griffin 2023; US Census Bureau 2020).

This paper is based on exploratory research and uses an intersectional analysis to understand how the transition to electric fleets affects students with disabilities across various underresourced communities and geographies, particularly rural, Tribal, and communities of color. Given that this group is predominantly impacted by overlapping issues of school bus segregation, poverty, and heightened air pollution, the paper aims to articulate their specific needs and recommendations for an equitable, accessible, and just transition to ESB fleets.

Background

In the United States, roughly 20 million children are bused to school each day (School Bus Fleet 2020). About 15 percent of K–12 students, or about 7.3 million children, have a disability (Schaeffer 2023). Integrating disabled students into the public schooling system has been common practice for less than 50 years, since the Education for All Children Act in 1975. Prior to 1975, students with disabilities were often in segregated schools, if in school at all (Dudley-Marling and Burns 2014).[ii] Despite this law’s intent to bolster school inclusion of students with disabilities, many disabled students are still segregated in bus routing—they are subject to separate buses (smaller, shorter buses for disabled students) and longer trips than their nondisabled peers (Howley 2001; Ross et al. 2020).

People with disabilities, including students, experience a variety of inaccessibility issues while riding diesel buses that are likely to remain if not addressed in the transition to electric fleet vehicles. Buses are often inaccessible because they lack a feature or support needed to ensure that a person with a disability can board, ride, and disembark safely. Some of these features include proper loading areas, proper tie-downs, space, and adequate training for and retention of bus drivers, monitors, and aides (Ross et al. 2020).

There are also new considerations for accessibility and access with an electric fleet of school buses, such as wiring and power lifts to accommodate wheelchairs and a quieter vehicle that affects people with low vision (BraunAbility 2023). In addition, accessible school travel for disabled students involves a multitude of stakeholders and considerations to plan for, including students, parents, school transportation board and transit agencies, teachers, and health professionals—all of whom play a role in creating accessible busing.

The gray literature and other research findings suggest that differences in bus routes and trip lengths for students with disabilities often exist because a disabled student might need supports that are not included on all school buses; this leads to the designation of a select few buses available to certain disabled students. Some disabled students may ride to school in a standard size bus (Type C or Type D buses), integrated with nondisabled students, or they may take specialty routed, typically lower-capacity buses (Type A buses) with other children with disabilities.

Segregation in school busing is not limited to students with disabilities and persists along racial and ethnic lines in the United States linked to location. Racially segregated neighborhoods persist today due to multiple federal and local government housing policies. Notably, the Federal Housing Administration’s redlining policies, beginning in the 1930s, did not insure mortgage loans in and near African American neighborhoods (Rothstein 2018). Today, segregation and disparities in property values and consequently wealth persist along racial and ethnic lines (Nelson et al. 2023). Local communities across the United States also inserted racial covenants into property deeds, which restricted people who were not white from buying or occupying certain parcels of land. Although the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer Supreme Court decision made racial covenants illegal, the neighborhood property ownership patterns continue to reflect this legacy (Mattke et al. 2022).

Busing has historically been used to increase integration for students of different races and different classes in the United States. However, the Brown v. Board of Education court decision did not have the expected impact on school integration. Instead, many white families subsequently moved to neighborhoods where the schools were primarily white, creating stark neighborhood and school segregation (Logan et al. 2017). To address this, a second lawsuit determined that school busing could be used to support integration by busing students outside their district (SCOTUS 1971). While both Brown v. Board and integrative school busing were meant to reduce racial segregation for students, schools in the United States continue to be racially segregated (GAO 2022). Thus, students of color with disabilities often experience dual forms of segregation in school busing.

For instance, Cordes et al. (2022) and the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA 2017) found that students with disabilities and students of color experience longer commutes than white and nondisabled students, illustrating that continued segregation of students with disabilities and students of color on school buses with longer commutes can negatively impact student health due to increased exposure to air pollution. Other issues can increase general commute times, as seen in 2022, when the Chicago Board of Education noted that a driver shortage deprived over 1,200 disabled students of school transportation, and over 350 students with disabilities had to endure school commutes of over 90 minutes, compared to 80 percent of routes with an average trip of 39 minutes (Peña 2022). Long commute times have been linked to inadequate sleep and other potential negative outcomes among students, which could exacerbate or create issues of disability for student populations (Voulgaris et al. 2019; Cordes et al. 2022).[iii]

Additionally, bad air quality is shown to have negative effects on the health of children and youth, as well as later in life (Liu and Grigg 2018). Increased exposure to air pollutants can cause respiratory disabilities, and increased exposure in bus cabins can particularly impact children with respiratory disabilities such as asthma, which is found in 4.5 million children in the United States (CDC NCEH 2023). Most of those disabled children (52 percent) live below the poverty line, where Black and American Indian or Alaskan Native children have the highest representation (CDC NCEH 2023).

Today, a move to electric fleets presents another opportunity for integration and increased equity in our schooling systems for students with disabilities, particularly those of color and who live in underresourced neighborhoods. The neighborhoods with the worst air quality are often where the poorest and least-resourced children reside (Morello-Frosh and Jesdale 2006; Konkel 2015). They are often children of color and may already have disabilities. Since 60 percent of low-income children ride buses to school, a move from diesel to electric could result in reduced pollution exposure for students already experiencing poor air quality (FHWA 2017).

Disability justice (DJ) and environmental justice (EJ)

Due to systemic impacts of racism and ableism on students with disabilities, researchers have applied disability justice (DJ) and environmental justice (EJ) frameworks,[iv] which go beyond special education legislation and policies, to look at the justice elements involved in the transition to ESBs. They also investigate how to achieve an accessible and environmentally just transition in school bus electrification. Box 1 below delves specifically into the issue of raw minerals and mining’s role in the ESB transition within these frameworks.

Each framework calls for holistic approaches to the pursuit of justice, that is, meaningful involvement of communities in land use planning and adequate long-term investments. Investments can include due attention to community needs, environmental and social remedies, and sufficient funding. Municipal, state, Tribal, and federal investments can be used as a tool to improve built and lived environments. For example, funds can contribute to reparations for environmental harms, fixing sidewalk infrastructure, or enforcing regulations on businesses that produce hazardous conditions compromising community health and safety.

ESBs serve as one of many proposed remedies to address the damage caused by pollution, as evidence finds that children are particularly susceptible to the negative health impacts of diesel exhaust (Liu and Grigg 2018). Truly equitable deployment strategies should ensure investment in districts most harmed by emissions, while distributing innovative resources responsibly without repeating environmentally unjust practices and rolling out plans that include diverse disability considerations. ESBs present an opportunity to increase investment in communities of color, rural and industrial areas, and Tribal Nations. Furthermore, they can also offer a pollution-free mode of transit for the students with disabilities who live in these historically underresourced areas. Equity thus includes consistent commitments to accessibility across school transportation.

Box 1. A global glance

In line with environmental justice (EJ) and disability justice (DJ) frameworks, we must consider where raw materials come from that make the transition to ESBs possible. A focus on expanding transportation equity for students with disabilities also requires thoughtful national and global consideration of youth and adults with disabilities who are negatively affected by the rise of electric vehicles as an industry.a

Electric vehicle batteries are made from minerals extracted from the earth; this is not unlike fossil fuels, which have been extracted in mass quantities for decades. However, there are some legitimate concerns about the environmental and social conditions of mining sites for batteries.b Mining sites for battery minerals are often located near Indigenous People’s lands.c Approximately 85 percent of the world’s lithium reserves are located either on or near Indigenous land.d In the United States, the mining of lithium poses a significant threat to Tribal communities, as approximately 79 percent of the nation’s lithium reserves are situated within a 35-mile radius of Tribal reservations.e According to advocates, seeking free prior informed consent of communities located near or at extraction sites across the globe is essential.f Additionally, regulations are needed to limit extractive practices that exploit workers, pollute the air and water of nearby communities, and cause damage to local infrastructure.

Advocates have demanded that the call for electric vehicles not silence the stories and experiences of the people of the global majority who live and work in the very areas where minerals are extracted, with global majority being a collective term that refers to people racialized as Indigenous, African, Asian, or Latin American and/or as ethnic minorities despite constituting 80–85 percent of the world’s population.g Injury, disease, and disability caused or exacerbated by harmful resource extraction cannot be ignored, while the benefits of electrification in America are heralded. Indigenous environmental justice activists have called for land back and an end to extractive mining practices that disturb Indigenous burial grounds, destroy cultural artifacts, and/or impede access to traditional foods and medicinal plants.h

The Battery Passport, an idea formulated by the Global Battery Alliance, attempts to provide greater transparency about the battery value chain. The passports will ideally allow consumers to scan their electric battery to track and trace its material origin and the environmental impacts on communities across the value chain.i Although this approach does not resolve the lack of overall data concerning global disability impacts, it may offer an avenue for consumers to further advocate for increased accountability.

As acknowledged in both DJ and EJ principles, suitable remedies for harm must be primarily decided and assessed by those most impacted. Interventions, even with the best of intentions, can increase harm when implemented without invitation from or involvement by those most impacted.j ESBs are one of many options to help protect the planet from dangerous toxins released into the air by diesel-fueled vehicles. Nevertheless, advocates worldwide have advised that protection must also be extended to the people who reside on the land, breathe the air, and drink the water where resources are extracted.k

Sources:

a Agyei-Okyere et al. (2019); Chason and Godfrey (n.d.).

b Sawyer (2022).

c Sainato (2023).

d Owen et al. (2022).

e Block (2021).

f IHRB (2022).

g Campbell-Stephens (2021), 4–6.

h Siegler (2023).

i GBA (n.d.).

j First National (1991); Berne et al. (2018).

k RRI (n.d.); WRI (2024).

Legal context

Although state-level education policies may vary, the United States has passed a series of federal laws establishing transportation access rights and safety requirements for students with disabilities in K–12 and higher education. However, the authors’ review of literature and the statements of research participants suggest that many laws and regulations are either outdated or not monitored for compliance. A systemic analysis of these laws and regulations and their enforcement is needed.

In the United States, schools receiving federal funding are subject to Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which tasked the Department of Education (ED) with certain accessibility requirements in campus access (OCR 2023a, 2023b). This includes busing. The Education for All Children Act of 1975 was updated in 1999 with the passage of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), both of which establish a series of rights and processes for schools regarding serving disabled students in K–12 education. IDEA requires transportation for disabled students as a related service to a “free and appropriate” education (O’Neil et al. 2018). A student may have a transportation plan as part of their Individualized Education Plan (IEP) or a Section 504 agreement that lays out an overall plan for a student with disabilities’ access and education (OSERS 2000).[v] A transportation plan may include specific agreements for mobility training or transit aid for school and school activities. However, transportation plans are necessary but not sufficient to eliminate disability discrimination. For example, the New York Department of Education was found in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act in 2022 for excluding students with diabetes from field trips and other activities due to a shortage of nurses needed to accompany these students (DRA 2023).

Safety requirements for school buses fall under the Federal Motor Vehicles Safety Standards (FMVSS), enforced by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Amended over the years, the FMVSS includes disability-specific safety measures such as wheelchair lift installments and requirements for child restraint systems (NHTSA n.d.). These laws require elements such as tethers and anchors for student restraints based on bus weight (49 CFR § 571.225). The NHTSA provides additional training and guidance interpretation regarding school buses and disabled students, including on modifying vehicles and student restraints.

Despite legal safety requirements, guidelines, and training, not all students get the proper support they need on the bus or in the classroom. In recent decades, busing has been dangerous and even deadly for some children with disabilities. In New Jersey, a six-year-old wheelchair user died after having her airway blocked by her harness when her school bus hit a series of bumps (Alfonseca 2023). Lawsuits have been brought against schools in South Carolina (Newell and Dickerson 2022) and Michigan (Catallo 2023) after disabled children were attacked on their buses by other students or bus drivers. In response, young adults with disabilities have led their own initiatives for better, more accessible busing access (Martin 2023).

Transportation infrastructure, such as sidewalks and safe intersection crossings, are also of particular concern for students with disabilities. For disabled students walking, rolling, or waiting at bus stops, the conditions of sidewalks and the layout of crosswalks are a necessary consideration for safety and accessibility. Cities across the United States have spent millions in settlements due to inaccessible sidewalks and intersections that do not comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (O’Hagan 2021).

While current school bus systems continue to struggle to adequately serve students with disabilities, new legislation around ESB transitions has been introduced around the country, but they seldom include new measures regarding school bus access for students. Bills in states such as Illinois (HB2287) and Washington (HB1368) require that equity measures be taken where ESBs are purchased and used within low-resourced communities. Along with two separate local ESB laws in New York City, New York State has a requirement to transition to all ESB fleets (New York City Council 2021; New York State Assembly 2022). However, as of the spring of 2024, few programs offer additional funds for accessibility features per bus, New York and the EPA’s funding programs being among the first (NYSERDA 2024) (EPA 2024a).[vi] Further research is required to determine whether the additional funds per bus are sufficient to cover the costs of an accessible bus.

Additionally, we were unable to determine how or whether the EPA’s CSBP monitors compliance with Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. When we inquired about program oversight, policy guidance, and nationwide enforcement of disability integration throughout the Clean School Bus Program, an EPA representative replied via email, “It is important to the EPA Clean School Bus (CSB) Program to assist disadvantaged communities and vulnerable populations. Special needs students spend more time in and around school buses, resulting in these students breathing in higher levels of bus exhaust. To help mitigate this issue, EPA will be awarding additional funds for ADA-compliant buses equipped with wheelchair lifts under the 2023 CSB Rebates Program that was launched yesterday (September 28, 2023).”

While these programs are taking measures to address inequities in school districts, government agencies, school districts, and manufacturers don’t sufficiently or consistently track information about proactive policy and procurement measures that are inclusive of accessibility. Our research shows that current local and state regulations and guidance documents do not strongly incentivize or enforce the procurement of accessible ESBs.

Methodology

This paper examines the ways students and adults with disabilities are impacted by electrifying school buses and shares their recommendations for designing a transition that achieves equity and accessibility. For the specific research questions posed by the researchers, see Appendix B. The research approaches (see the next subsection) were designed in acknowledgment of Indigenous and Black feminist research methodologies (Smith 2012; Collins 2000). For example, research practices included sharing knowledge of previous experiences and worldviews, the use of dialogue to develop knowledge, and an ethic of care and personal responsibility with the knowledge and expressions shared during stakeholder interviews.

The recognition of diverse information sources is of particular importance among Indigenous and Black communities, whose histories and systems of knowledge are not always understood or recognized in academic and institutional research traditions and frameworks. Such inequities concerning the credibility of collective or shared wisdom also overlap with the erasure experienced by people living with disabilities (Gilroy et al. 2021). Both DJ and EJ recognize the importance of informed consent (Appendix C), leadership by those most impacted, interdependence, and sustainability. These principles are observed in this paper through a concerted effort to center the reflections and recommendations from diverse students and adults with disabilities. Participant views on the impacts, barriers, and best practices for achieving disability and environmental justice in school bus electrification are thus prominently presented throughout the “Research findings” section.

This working paper is an exploratory study rather than an exhaustive one. It is not a statistical synopsis of data concerning the impact of ESBs on disabled students. It is, however, comprised of narrative analyses intended to gather and present a multitude of perspectives steeped in the priorities, interests, and needs of disabled students.

Research approach

Researchers on our team gathered data and information through gray literature, semistructured interviews, online surveys, a facilitated discussion, and public records review of legal claims and public comments.

Across the research approaches, researchers selected participants based on a wide range of community recommendations, preestablished WRI relationships, and research-based outreach to key stakeholders. In all, researchers solicitated participation from over 70 organizations and individuals through email and phone calls. Our outreach included the following types of groups:

- Advocacy organizations, including disability-led organizations, identified as having a stake in the ESB transition

- Federal agencies connected to the ESB transition

- Civil rights law centers working on environmental and disability issues

- Manufacturers and dealers identified by WRI as bus companies most frequently used by school districts nationwide

- Medical research centers with expertise on health and disability

- Membership organizations:

- Outreach to parents through advocates in health, transportation, disability, education, and climate justice

- Outreach to students and other youth through networks of disability and climate organizations with youth programming

- School districts with geographic diversity identified through an existing relationship with WRI

- Unions connected to transportation services and the e-bus transition

Throughout the research, we categorized participants as “students or other youth” or “parents and professionals.” Due to the intersection of various adult participants as both parents and professionals, the researchers determined not to separate out those participants but instead keep them under one categorization that includes both parents and professionals.

A total of 24 individuals representing 16 organizations (Appendix A) contributed to the primary research (9 students and other youth and 15 parents and professionals). The small participant pool also reflects budgetary limitations, as each invitation included an offer to equitably compensate contributors for their time and insights ($50 for surveys and $100 for interviews or discussion). The guide and questions used for interviews, surveys, and the facilitated discussion can be found in Appendixes D (students and other youth) and E (parents and professionals).

- Interviews: Researchers conducted 12 one-on-one semistructured interviews via Zoom lasting 45 minutes to 1 hour (one interview had two representatives present). Researchers posed research questions and follow-up questions based on responses. At the conclusion of each session, researchers encouraged participants to contribute supplementary research questions that helped to uncover new analytical frames and bridge knowledge gaps—a DJ research methodology that centers the most impacted.

- Surveys: Researchers received a total of 6 surveys (3 for students or other youth and 3 for parents and professionals). In consideration of various communication needs, preferences, and time constraints, researchers offered an online survey option through Google Forms. Researchers created two versions of the survey, one for students or other youth, and one for parents and professionals (with and without children with disabilities).

- Facilitated discussion: Researchers facilitated one discussion with 6 student or other youth participants via Zoom over 1.5 hours. Designed to generate more open conversation and commentary, the discussion was intentionally structured for a small group. Researchers thus adjusted the questionnaire with a more conversational frame. The collaborative format offered participants a unique opportunity to engage in a collective visioning exercise. Participants discussed the various benefits, barriers, and best practices related to people with disabilities and the use of ESBs.

- Legal claims and public comments and testimonies: Researchers conducted an expansive literature review, which also included available legal complaints, public comments, and written and oral testimonies (Civil Rights Division 2022, 2023) regarding disability and ESBs since most disability rights are primarily protected through complaint-driven processes (US Access Board n.d.; Southwest ADA Center 2018). Researchers used key search terms such as “disability,” “special education,” “school bus,” and “transportation” on repositories such as the Federal Register, Department of Justice, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and state and local government entities that recently purchased ESBs (e.g., NYSERDA; Montgomery County, Maryland). Researchers also searched press stories and reports on busing and students with disabilities.

Research limitations

Researchers encountered two timing and data limitations. First, the research period occurred during the summer of 2023, when schools were not in session. Therefore, it was difficult to confirm facilitated discussions with educators, parents, and advocates. Although this paper shares findings captured from 24 individuals across 16 organizations, the sample size, which is typical in qualitative analysis, is not representative of all stakeholders in the ESB transition. Second, there is a lack of consistent data tracking on disabled students and accessible electric transit. School districts, manufacturers, and bus dealers alike were only able to confirm that ESBs have the capacity to be outfitted with accessible features but did not have national data on the number of accessible ESBs in use at the time of writing.

Research findings

The following subsections summarize the research findings. Each subsection includes reflections, ideas, and key findings for an accessible and just school bus transition based on research participants’ context, lived experiences, and professional expertise from the interviews, surveys, and a facilitated youth discussion. For access purposes, participant insights are presented in short summary paragraphs, bulleted lists, and direct quotes within each subsection:

- Inclusion, barriers, and improvements

- Intersectional, environmental, and infrastructural considerations

- Current transportation access challenges and technology concerns

- Educational impacts

- Improving accessibility

- New opportunities and multipurpose uses

Inclusion, barriers, and improvements

“Please don’t wait to think of marginalized folks until the last minute! Everyone deserves to have access to transportation. Electric buses need to accommodate everybody,” one youth survey respondent explained.

Youth participants outlined their main challenges with school transportation, including not being included in decision-making processes. They expressed that students and families with disabilities are often not meaningfully consulted, resulting in inaccessible transportation infrastructure and programming. Participants noted that the inclusion of disabled students through accessible buses is often seen as a choice rather than a requirement. Inequity can be seen in the deprioritization of transportation programming and infrastructure for disabled students. Additionally, youth participants pointed to a lack of versatile and accessible design features on school buses.

“Have advisory groups with disabled students and adults, and actually include that group in decision-making or require their stamp of approval,” recommended a youth survey respondent. “Consistently asking, ‘Is this as accessible as possible?’ and/or ‘How are disabled people affected by this decision?’ throughout the process would also help. Ensuring accessible school buses are transitioned to electric at the same rate or better compared to regular school buses is important.”

Key Findings

Note that some of these findings apply across all school bus fuel types.

Students and other youth

- Consider the needs of disabled students during bus design (manufacturers) and transportation programming (school districts). Elevate the consideration of disabled students in these processes, and ensure that they are not an afterthought or deprioritized, in other words, include them as routine testers of new access features, ensure that they are not the last to receive access to ESBs.

- Consult students on their needs. Ask students what would make them feel comfortable and included when riding buses. Involve students in conversations and decisions on school district changes to buses and transportation.

- Appoint youth to transportation or policy committees or create student advisory boards at all levels of the transition. Design inclusive committee composition and protocols: explain processes and procedures, provide equal voting power and accessible meeting formats, include more than one youth representative (as one person is not representative of an entire student body), and include representation from students with diverse disabilities.

- Provide ongoing communication and feedback with students and families during and after the transition. School districts should provide meaningful forums for including students and their families to provide feedback on transportation issues and decisions on an ongoing basis, such as through advisory councils and regular meetings. This contrasts with the standard practice of collecting information during one-time focus groups and surveys.

- Include accessibility features on every bus. Every student participant in the facilitated discussion strongly believed every bus should have accessibility features such as a wheelchair ramp and lift, so all students always have access to all buses.

Parents, professionals, and advocates

- Document transportation changes and any new student needs in Individualized Education Plans. Share documentation with all relevant staff.

- Some parents, professionals, and advocates also agreed that all buses should be accessible to all students.

Intersectional, environmental, and infrastructural considerations

“I wonder about energy efficiency with bus routing for students in the more rural parts of the district,” reflected one youth survey respondent. “I worry about pushback on [bus electrification] and taking climate action even though our community has been affected by the impacts of climate change already [and] inequitable transitioning of buses across the district and state.”

Youth participants noted several accessibility challenges in addition to environmental and infrastructure problems they have observed in communities of color and low-income areas. Participants opined that these demographics face similar issues with inadequate transportation infrastructure, elevated air pollution levels, and other climate-related impacts because of discrimination and unequal access to critical resources. “The transition to electric school buses is so important when we think of climate crisis and the effect of the climate crisis on students with disabilities,” another student said during the facilitated youth discussion.

During the facilitated discussion with students and other youth, participants shared lived experiences and observations about how students from low-resourced neighborhoods in urban and rural areas sometimes deal with parallel problems, such as unsafe or absent sidewalks or roads on school commute routes. Participants also wondered whether emergency planning was adequate. Furthermore, they worried that parents who work long hours or multiple jobs may struggle to attend Parent Teacher Association (PTA) meetings to advocate for infrastructure improvements. Consequently, students believe that parents in underresourced communities deserve appropriate accommodations and dedicated advocates that focus on transportation access for students and families.

Youth participants across multiple geographic backgrounds relayed concerns that more affluent areas may receive access to ESBs before students in areas that need them most: low-income, immigrant, farming or other rural, industrial, and urban areas, as well as Indigenous lands. When clean transportation options are unavailable, Tribal and disability rights and justice organizations stated that rural communities feel compelled to accept available forms of transportation, even old diesel buses (Brown and Curran 2023). This lack of transportation access underscores the environmental trade-offs low-resourced communities must contend with when denied access to sufficient funding for clean transportation and infrastructure.

“Many of the roads on the Navajo nation are unpaved,” explained an attorney with the Native American Disability Law Center, “and so families will get down to a central meeting place because it’s paved and the school bus doesn’t have to go off of the main highways. Because if it rains or it’s snowy, these unpaved roads can get very muddy. I’ve had clients who have missed a week of school because the family truck just cannot get out of the property. We’ve had issues where people who use wheelchairs are essentially not able to get out of their homes and get down to the school bus. And so, kids are missing school.”

Students experiencing houselessness also face unique challenges, as school bus routes often do not serve those students. A representative from Soderholm Bus and Mobility, a national distributor of school buses and vans, acknowledged that when students with disabilities living in shelters or encampments do not have access to transportation, they can easily fall behind. This participant cited the experience of Micronesian families who recently immigrated to Hawai’i under the Compact of Free Association with Micronesia. Families moved for housing and jobs, and encountered many social, political, and economic barriers that left many homeless (Lincoln 2015). Some individual schools are filling the gap using creative solutions such as purchasing multipassenger vans, which has helped increase but not resolve the attendance rates of students experiencing houselessness. Noticeably, houseless students with disabilities are impacted by such transportation gaps. Disabled people disproportionately experience chronic homelessness, making up about one-third (31 percent) of all individuals experiencing homelessness in 2023 (HUD 2023).

Adult advocates also remarked on additional infrastructure concerns associated with the electric transition, including street damage caused by an increased number of heavy electric vehicles.[vii] A mobility access advocate explained that potholes and street cracks also create safety risks for disabled students. At the same time, Multiple participants also observed that when diesel buses are idling as students who use wheelchairs wait to be lifted, it can further expose youth, drivers, and care aids to more tailpipe admissions. This is yet another key concern for students and adults on the bus with respiratory conditions. Districts hoping to gradually phase in ESBs thus face dual challenges. They face environmental health challenges associated with diesel buses currently in use and the financial challenge of securing new ESBs that are equipped to transport all students.

A representative from Blue Bird, a large school bus manufacturer, offered additional insights: most of the ESB challenges they have observed are related to charging infrastructure, limited battery range that may not serve longer routes, and the cost of accessible ESBs: “There is a challenge related to the range of an electric school bus that can limit its usability in rural or Tribal areas that have longer routes. In addition, the charging infrastructure can be very costly to install. Many school bus facilities do not have the available power to install chargers, which can require costly upgrades from the local utility.” This participant went on to note that cities and school districts without ample transportation budgets can address some of the above challenges by applying for additional state and federal funds, such as the EPA’s CSBP. Much of this funding is earmarked for rural, low-income, and Tribal school districts.

Key Findings

The findings here consist of participants’ concerns and considerations regarding the ESB transition. Note that some of these findings apply across all school bus fuel types.

Across all participant categories

- Disproportionate impact of climate crises on people with disabilities in general, and people of color with disabilities in particular.

- Lack of adequate emergency plans for bus breakdowns, or specific plans for students with various disabilities.

- Concern about an unequal transition to ESBs between affluent and underresourced areas.

- Inadequate transportation access in low-income areas and communities of color, which students noted are demographics that often overlap.

- Restrictive PTA schedules that exclude parents with various work schedules and a lack of available accommodations for disabled parents.

- Unsafe and absent infrastructure like walkable sidewalks in rural and immigrant communities.

- Higher air pollution in poor neighborhoods.

Parents, professionals, and advocates

- Absence of transportation access for students experiencing houselessness.

Current transportation access and technology concerns

“Just because something is not broken, does not mean it is accessible,” one student explained during the facilitated youth discussion.

Student and other youth and parent and professional participants identified several concerns about perpetuating current transportation access and technology challenges. Challenges include malfunctioning or inconsistent availability of accessible transportation, limited resources, and early adoption burdens. Additionally, Box 2 below examines paratransit’s role in transporting students with disabilities.

Participants pointed out several accessibility issues with malfunctioning or outdated wheelchair lifts on their current diesel buses. Many school buses have lifts that require students with wheelchairs to navigate onto the lift backward. This is a problem for students with wheelchairs who also have dexterity difficulties or other disabilities related to sight and hearing. Navigating backward is also challenging during intense weather conditions such as rain, ice, and snow—all of which are increased by the ongoing climate crisis. One student said they encountered transportation access issues at least three times a week. Before the school day even begins, students with disabilities report dealing with barriers including malfunctioning lifts, broken wheelchair securements, and prolonged wait times when staff are unfamiliar with access features on buses. Participants voiced concern that if these issues are not addressed in the transition, they will continue with the new electric models.

Adult participants stated that drivers and paraprofessionals and caregivers with disabilities and access needs should also be considered throughout the transition. Participants observed that back injuries and other physical health problems have impacted bus drivers due to high vibration levels on diesel buses. One participant explained that whole-body vibration happens when buses don’t have independent suspension. Drivers and passengers on Type D buses, whose driver seats are near the front wheel, can endure magnified G forces to the body. “Electric buses offer a smoother and less bumpy ride for everyone, including bus drivers,” noted an Amalgamated Transit Union representative. “Improvements such as these can contribute to better work conditions for drivers and will ideally lead to greater availability of skilled drivers [and] mechanics.”

“Back injuries for bus drivers and truck drivers are incredibly high,” the union representative continued. “It’s because of how buses and trucks are designed. They don’t have to be that way. If buses were made to work better for bus operators, people would stick around in those jobs longer, and you wouldn’t have as many staffing shortages. You wouldn’t have people calling out sick as often or going on as much leave.”

The Amalgamated Transit Union representative went on to echo student concerns regarding the use and upkeep of ramps and lifts. They explained that inaccessibility challenges are also caused by absent workers. “Inaccessibility for school buses is also when buses don’t show up. The number one reason for that is because they don’t have a bus operator, or maybe a monitor. They [schools] can’t send the bus out. And some of that, of course, is the ability to attract and retain skilled mechanics. There needs to be training also for maintenance staff to make sure that they know what they’re doing when it comes to wheelchair lifts and battery electric buses when districts transition.”

One school official reflected on resource limitations and how prioritizing accessible buses in the transition could help with driver retention: “In our district, our goal was to target routes that transport students with disabilities. However, I was informed that we needed to purchase the bigger buses. Typically, we transport students with disabilities in smaller buses. I wonder if there’s a way to strategically indicate the need to allocate some of those resources to transport the disabled students. I also see it from the lens of retention. If we have nice buses, our drivers will be incentivized to stay within our district. Therefore, we will have the available resources to ensure we can meet the needs of our district.” At the time of writing, we do not have the necessary data to know if the ESB transition is happening at the same rate across the various bus types. Further research is needed.

Additionally, one parent and disability justice advocate explained how some school districts deal with multiple transportation access barriers, such as limited budgets and staff shortages: “Students of color with disabilities and/or disabled students who are low-income or in geographically low-resourced areas, often reside in school districts with limited funds and as such, are less likely to be in a position to be early adopters of bus electrification. They might face a shortage of bus drivers and might have to contend with an already aging fleet of buses. They are also more likely to encounter bus sharing as well. The public might have safety fears or concerns due to limited familiarity with bus electrification. For decision-makers, cost could be a concern, even though in the long run this will be a worthwhile investment that is better for the environment and cost-effective. But because there will need to be sufficient investment of initial and ongoing resources to make things happen, the high short-term costs could be a deterrent.”

The recent policy prioritization of underresourced communities in ESB funding could address resource limitations, but participants also emphasized that protective measures for early technology adopters should accompany the ESB transition. A representative from New York Lawyers for the Public Interest described their policy platform to prioritize disadvantaged communities: “We found that in some cases you have hundreds of diesels and gasoline school buses clustered together. And they are in the same environmental justice communities where other pollution sources are also concentrated. . . . Our policy push has been for the city and the state not just to mandate, as they have, an all-electric bus fleet by 2035 but to prioritize getting electrification to happen first in disadvantaged communities that are most impacted by the current polluting school bus fleet and other pollution sources.” Participants supported this prioritization, and added this should be “priority without penalty.” The burdens of being the first to receive and test new technology can be costly and time-consuming for districts, which could experience the “early adopter tax,” or the fact that new technology costs more when released and includes defects that get resolved in later models (Rogers 1962). Advocates noted that being first also involves the added pressure of executing all plans perfectly for fear that any perceived failures will be used as a convenient excuse to deprioritize impacted communities in the future.

Box 2. Paratransit

When available, paratransit has become yet another mode of transportation for students when public and school transit options prove to be inaccessible. Paratransit vehicles typically consist of door-to-door transport on multipassenger vans equipped with wheelchair lifts and/or ramps. Paratransit programs can also be administered through discounted use of taxicab services. The National Aging & Disability Transportation Center defines the relevance and reach of paratransit: “The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires public transit agencies that provide fixed-route service to provide complementary paratransit service to people with disabilities who cannot use the fixed-route bus or rail service because of a disability. The ADA regulations specifically define a population of customers who are entitled to this service as a civil right.”a

Similar to public transit and school buses, paratransit is not without its challenges. Extensive wait times, ride restrictions based on city budgets, and no service at all in many rural and Tribal areas are a few of the issues and inconsistencies associated with paratransit systems.b At the time of this writing, we were unable to confirm any city paratransit systems that have transitioned to electric buses.

Sources:

a NADTC (2023).

b Venkataram et al. (2023).

Key Findings

Note that some of these findings apply across all school bus fuel types.

Students and other youth

- Unreliable ramps and lifts that frequently malfunction, creating unsafe and unreliable conditions.

- Insufficient wheelchair space for multiple students with disabilities on most buses. This is a design flaw that assumes multiple disabled riders won’t be present at once.

- Sound and scent overstimulation from vibration, noise, and inhaling diesel fumes. These pose health and wellness challenges for riders and operators, such as migraines, dizziness, asthma attacks, panic attacks, or disorientation.

- Safety risks caused by untrained, inexperienced, or impatient bus operators and bus monitors.

Parents, professionals, and advocates

- Efforts to prioritize disabled students during the transition without imposing harms from adoption of new technologies.

- Concern about financial cost and community readiness.

- Need to ensure bus operators’ safety and wellness.

- Repetition of inaccessibility challenges present in diesel fleets.

- Irregularities around existing infrastructure.

- Incorporation of cognitive accessibility and language justice in all communication.

- Adoption of universal design principles, including seat fabric and texture, wheelchair-dedicated spaces, climate control, high-quality ventilation, lighting, and noise regulation.[viii]

Educational impacts